Here’s another grammar trick (from Grammar Girl) to help you know when to use “that” or “which.”

“Which” is followed by a clause that can be deleted without affecting the sentence.

Example: She passed through a metal door—which locked closed behind her—and instantly recognized the nicer furnishings in the hotel.

This sentence works without the “which” clause: She passed through a metal door and instantly recognized the nicer furnishings in the hotel.

“That,” however, forms a clause or part of a sentence that cannot be deleted. (This sentence is a good example.)

Example: “It’s one thing that separates us from the children of Seth, who do not really recognize any common brotherhood amongst themselves.”

It doesn’t work without the “that,” though: “It’s one thing from the children of Seth, who do not really recognize any common brotherhood amongst themselves.”

Grammar Girl admits that there are times when you can “which” instead of “that” (not sure when), but you should never use “that” instead of “which.”

Grammar Girl admits that there are times when you can “which” instead of “that” (not sure when), but you should never use “that” instead of “which.”

And here’s a handy way to remember: You can kill the witch, but not the “that.”

I also found out the answer to the drug/dragged question on Grammar Girl. “Dragged” is always correct, “drug” never is. However, “drug” is commonly used in the South (which explains why I was confused about it), so if you’re writing Southern characters, “drug” would have a legitimate use in the dialog (along with “ya’ll” and “ain’t” and “shit fire and save the matches”).

Insert Grammar Rant Here

Some of the comments on the “dragged/drug post were… um… interesting–including the person who was adamant that only uneducated people use the word “drug,” and that people needed to be forcibly educated and such ignorant, incorrect word usage stomped out.

As a Southern person, I take offense at such statements. It’s one thing to say that X is considered correct, but another thing entirely to assume that people who say Y are idiots. One of my pet peeves in life is having people treat me like I’m an idiot (or, possibly worse, give me some sort of backhanded compliment like I’m smarter than they expected) just because I have a pronounced Southern accent.

Competing to catch a pig (this image from the Foxfire Heritage Festival in Georgia) is an old medieval game.

English is not math. In math, 2+2 always equals 4. It can never equal anything else. Language, however, constantly changes. In 1900, “gay” meant someone who was happy and carefree. Today it means a homosexual (particularly, but not exclusively, a male homosexual).

One commenter found evidence that “drug” as a past tense of “drag” was probably in use in England in the middle ages. (Let’s face it, “hang” becomes “hung,” unless you “hanged” someone as a form of execution). This would explain why “drug” is still a favored word in the South. Some linguists think that the Southern dialect (both the way we pronounce our vowels and certain grammatical choices, like “ain’t” and “drug”) is a holdover from 17th century England. There is evidence that Shakespeare’s players spoke more like Southern people than modern-day Englishmen. Southerners’ ancestors tended to come from the rural parts of England (damn near everyone in my family tree did), Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. They brought their accents with them in the late 1600’s and early 1700’s (and their music; traditional Irish folk music is almost indistinguishable from traditional bluegrass), moved into small, isolated communities, and there they stayed.

“Forms thought to be substandard today are actually the outmoded standard of yesterday.” —The Dialects of American English

“The speech of the Ozarks comes closer to Elizabethan English in many ways than the speech of modern London.” – -Mario Pei, modern linguist.

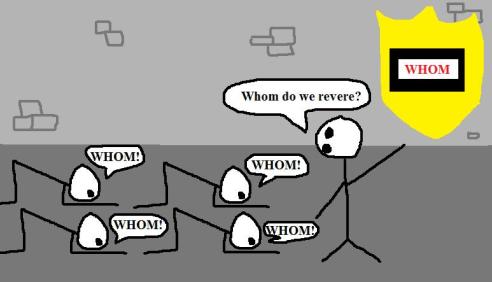

We’re not ignorant; we’re historic. Okay, maybe that should be “archaic.” But that doesn’t equate to ignorant. After all, “whom” has become a rather archaic word, but the Disciples of Whom would bristle at the thought that they are ignorant because they cling to a word that modern English speakers have discarded.

We’re not ignorant; we’re historic. Okay, maybe that should be “archaic.” But that doesn’t equate to ignorant. After all, “whom” has become a rather archaic word, but the Disciples of Whom would bristle at the thought that they are ignorant because they cling to a word that modern English speakers have discarded.

English is a Living Language

Although some people seem to want to homogenize the entire English language and then freeze it in amber for future generations, it is impossible to do. English is a living language, and words must come into use and go out of use. Likewise, there must be regional variations.

For one thing, as I mentioned above, each region in the U.S. has its own history and its own unique blend of immigrants. In the South, we had almost no German or Nordic immigrants, but they were quite common in the Northern States, such as Pennsylvania and Minnesota. Those people’s accents affected how they (and their descendents) pronounce English. It also created unique words peculiar to that area (no Southern native has any idea what a lutefisk is anymore than a Minnesotan knows what chittlins are). The same difference shows up in the great pop versus soda versus coke debate.

For one thing, as I mentioned above, each region in the U.S. has its own history and its own unique blend of immigrants. In the South, we had almost no German or Nordic immigrants, but they were quite common in the Northern States, such as Pennsylvania and Minnesota. Those people’s accents affected how they (and their descendents) pronounce English. It also created unique words peculiar to that area (no Southern native has any idea what a lutefisk is anymore than a Minnesotan knows what chittlins are). The same difference shows up in the great pop versus soda versus coke debate.

Curiously, spiritualism says that every area has its own unique vibrations/magnetic field/energy, and the people who live in that area will be affected by that–even down to the way they speak. (Most, if not all, Native American traditions–and even Judaism–teach that there is a definite spiritual link between people and land.) If this is the case, then it would be silly to think that you could truly homogenize English grammar, much less dialects. (This might also explain why an Ohioan friend of mine–who had long lived in the South–caught herself saying “fixin’ to.”)

In other words, a living language changes. This is what makes it living.

Latin is a dead language because no one speaks it as an everyday language anymore, so it doesn’t evolve. Hebrew used to be a dead language, too, but around the turn of the 20th century, when the dream of Israel was growing in strength, a man by the name of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda decided that Jews needed to reclaim their mother tongue. (Hebrew was like Latin at that time–a language only of prayer and religious documents.)

Eliezer began speaking Hebrew at home and teaching his wife and children. But he quickly found that there weren’t words in Hebrew for modern things like ice cream, automobiles, airplanes, grocery stores, etc. The language had never evolved to keep up with the times. So he set about making up all the new words it needed to function in the modern world. (Here’s a problem you might not think of: There were real no curse words in ancient Hebrew. Modern Israelis have re-purposed some old Hebrew words (the word for a female prostitute was well-known, but was not used as an insult before modern times, and was never coupled with “son of a….”) and borrowed from Arabic and English.)

A piece of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The arrow points to the name of God, which was still being written in very ancient Hebrew letters. The other letters all have their modern shapes.

Eliezer campaigned hard to get Jews to speak Hebrew as an everyday language, and by the time the country was founded in 1947, Hebrew was an official language. (This is really remarkable, because one, Hebrew fell out of use before the Romans expelled the Jews from Judea–Jews during the Roman period spoke Aramaic almost exclusively–so it had been a dead language for more than 2,000 years; two, huge numbers of European immigrants were fiercely loyal to Yiddish and didn’t want to speak anything else; and three, it’s the only dead language to ever be revived in human history.)

Since that time, Hebrew has started to evolve away from Biblical Hebrew. While an Israeli child can read the Dead Sea Scrolls and understand them (they’re some 2,000 years old), the grammar now seems archaic (just as the grammar and spelling in a 1603 King James Version Bible is understandable to us, but archaic).

Oh, the irony! Vivian Leigh was English. She studied Southern dialect with a linguistics professor from the University of the South at Sewanee.

So, while something may or may not be grammatically correct now, that doesn’t mean that it was incorrect in the past (“ain’t” was a perfectly acceptable word in the 18th century and before), and that doesn’t mean that it will be correct in the future. So don’t judge a person’s intelligence based on how they speak English; you may someday find that your cherished words and grammar style are gone with the wind, too.

I like all of this, Keri. Grammar Girl saved my butt on numerous occasions, and it was a eureka moment when the thats and whiches were finally understood.

There are a lot of times when you can drop something out of a sentence or substitute another word and test how it works.

For instance, if you can drop a phrase out of a sentence and still have the sentence make sense, not only should you use “which” (if applicable), but that entire clause needs to be separated by commas. Of course, there are many other times to use commas, but that’s at least an easy one to figure out.

Commas. No matter how much I look up their usage, I still get confused about some of them. I search commas more than any other grammar help.

They’re not easy because their usage is fluid. People in the 19th century used them much more than now.

For instance, starting a sentence like this used to always require a comma, but now I’m seeing people going without them.

In general, if a clause can be cut out of the sentence with no major loss of information, it needs to be off-set by commas. If a clause following a conjunction is not a stand-alone sentence, then it generally does not get a comma. Conversely, if the clause following a conjunction is a stand-alone sentence, it will almost always need a comma (if you go without the conjunction, then you need a semi-colon).

I tend to comma like I read out loud: a comma everywhere I take a breath. There are definitely places where commas are optional and putting them (or leaving them out) will affect how you read the sentence.

I had to look up comma-ing the word “too.” Grammar Girl herself said that is a case of an optional comma. You can offset it completely, partially, or not at all–all depending on how you want the person to read the sentence.

Complete offset: He had a small bald spot on the back of his head, too, but it was usually hidden under his yarmulke.

Partial Offset: Jean was there too, but he didn’t speak to either of them all evening, and the silence was strained and uncomfortable.

None at all: Despite herself, Kalyn laughed too.

In the second sentence, the comma before the final conjunction is optional. The clause following it can be a stand alone sentence, which means it can have a comma, but because it references the preceding part of the sentence, it’s not required.

“Marie had gone to look for Jonas as soon as she had shown all of them to their rooms, but he had not gone back to his house, and no one had seen him since he had left the meeting.”

The final comma is really necessary because the last part of the sentence can stand alone AND it’s not directly related to the preceding clause. Not going back to his house and not being seen since leaving the meeting are not directly related (whereas, in the preceding example, not speaking and the silence being uncomfortable are directly related). Also, the longer the sentence, the easier it is to read with commas.

So, to some extent, commas are a touchy-feely sort of thing. Read your sentence out loud and decide if you want your reader to pause and hear the clauses separately, or if you want them to run together into one idea.

This refers to the accents and dialects spoken in the country of Wales. The speech of this region is heavily influenced by the Welsh language, which remained more widely spoken in modern times than the other Celtic languages.

regarding the coke vs. pop issue—-if’n you had been in east tennessee you might have been drinkin’ a dope (for coke/cocola)

I’m from near Chattanooga and my husband’s family is from Knoxville, and I’ve never heard that before. Dope is always marijuana.

How far east are we talking about?

GOOD POST. “AIN’T” IS STILL USED IN SOME HIGHER SOCIO-ECONOMIC BRITISH CIRCLES.

So happy I could cry!

I’ve been more relaxed about “ain’t” since I saw it in a Shakespearean play, and saw it in numerous 18th century American papers. It is a word; it’s just not particularly liked.

I’m printing your comma reply to me and keeping it on my desk. Some commas may be “old school,” but I’m keeping them – such as a comma before and after “too.” I think when I start cobbling clauses together, I am my most confused. I tend to re-write and break apart sentences when commas trip me up. However, I do prefer to use as few commas as possible. Sometimes, I read something, and the writer has used so many commas, they are distracting. … I also realize I’m hanging around your blog tonight. 🙂 There is no need to respond to anything I’ve left here tonight!

I like it when people hang out on my blog and chat! I’m introverted in real life (I think most writers are), so this is how I interact with people.